Working with Indigenous Peoples and local communities: 8 Lessons from GCBC Research

Research conducted in partnership with Indigenous Peoples and local communities (IPLCs) is increasingly shown to develop stronger, more inclusive understanding of our shared environment¹. By grounding evidence in local realities and lived experience, such approaches improve the relevance, impact, and resilience of interventions.

At GCBC, we place strong emphasis on incorporating local and Indigenous knowledge into the development of scalable and policy-relevant solutions. However, the role of IPLCs in research partnerships is complicated. In many projects, they may simultaneously be the subjects of research, the implementers of research, and the expected beneficiaries of the solutions developed.

At the same time, the relationship between researchers and IPLCs may be characterised by very distinct priorities, significant power imbalances, and different ways of interpreting the world.

Recognising this complexity, GCBC invited grant recipients to share their reflections on conducting research with Indigenous Peoples and local communities, in particular highlighting the insights they were gaining in the process. Specifically, we asked:

What has the project learned about the necessary conditions to secure the engagement of local and Indigenous communities in the research?

The responses touch on a number of interconnected issues. Eight main insights emerged and are summarised below.

1. Early and Continued Engagement

Our projects emphasise that partnerships with Indigenous Peoples and local communities should begin early and continue throughout the research process.

Engagement should go beyond simple consultation.

For our project in Panama, for example, the proposed research emerged from a year-long consultation process, grounded in a much longer-standing relationship between one project partner and an Indigenous council².

In Ethiopia, ongoing dialogue between researchers and communities strengthened mutual understanding and helped reduced the risk of misconceptions³. A similar approach was taken by our researchers in Madagascar, where Indigenous Peoples and local communities were regularly updated on research progress and invited to evaluate the successes and challenges⁴.

2. Community-Led Research Framing

Much social and natural science research starts with a tightly defined set of research questions, the framing of which is usually led solely by researchers. Our projects demonstrate how this approach must be reconfigured to accommodate IPLCs perspectives and needs.

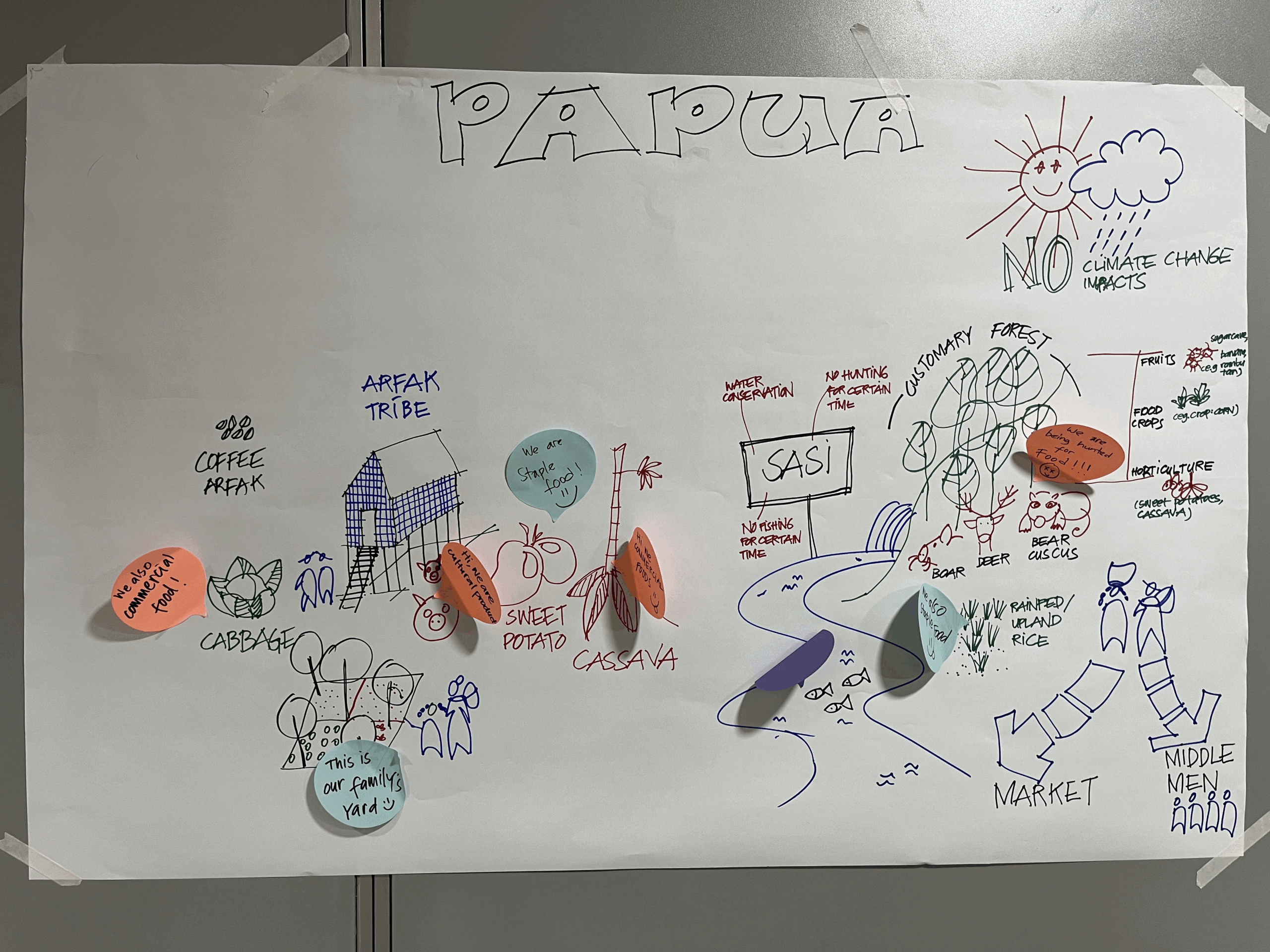

Experiences from Colombia highlight that meaningful engagement in research needs to be about more than just involving IPLCs in data collection – it begins with co-creating meaningful research questions that matter to the communities themselves⁵. This is supported by work in Indonesia which suggests that engagement with IPLCs is dependent on research questions being informed and shaped by them from the outset⁶.

The process of defining research questions can potentially be complex, as research in Peru and Ecuador reveals. Farmer-led research often follows its own logic and pace in ways that differ from formal institutional projects⁷.

Yet, experience from Ecuador and Viet Nam suggests that ultimately communities are more willing to engage in research activities when research agendas and research questions align with their needs.

3. Informed Consent

In our work with IPLCs, consent, often expressed as Free, Prior, Informed Consent (FPIC), is a fundamental principle – and sometimes legal requirement. For example, for a project working in Malaysia, engagement is based on a voluntary agreement made with full knowledge of the project’s scope, purpose, risks, and benefits⁹.

Gaining consent is not always a quick process. In Cambodia, trust and flexibility were required to gain consent and community support for the project. As a result, communities valued the opportunity to determine the project’s focus and to highlight the importance of their own knowledge¹⁰.

In some cases, FPIC is not just as an ethical necessity but also of practical importance too. For instance, a project in Ecuador found it fundamental for reinforcing community confidence and fostering long-term collaboration¹¹.

4. Communications and Transparency

Good communication with IPLCs emerged as a key attribute of project implementation. Our project in Guatemala detailed communication’s importance for a range of project needs including how information is to be used, how impartiality in data collection is assured, and how communities retain decision-making power over research that affects them¹².

The importance of communications tailored to specific groups was highlighted by one of our projects in Ethiopia that used communication approaches specifically designed for different groups to ensure gender and social inclusivity¹³.

However, good communication goes beyond the flow of information between researchers and IPLCs. Experiences in Colombia and the Dominican Republic suggest that projects can also act as a communication channel between members of the community¹⁴.

5. Power Dynamics

Attention to power dynamics was important across various contexts. In Malaysia this required awareness of researchers’ own effect on those dynamics and the need to continually reflect on their power and impact on IPLCs¹⁵.

In Malawi and Uganda, power was a consideration in the implementation of fieldwork, where workshops required taking language and social dynamics into account to encourage the engagement of community members¹⁶.

Understanding power dynamics was also critical in relation to outcomes and ownership with our project in Peru. This highlighted the important role of good facilitators in ensuring that project participants, including women, whose involvement may be constrained by household power dynamics, can take ownership of the research and engage with confidence¹⁷.

‘One aspect of the project is to examine local governance structures and their power dynamics to support the effectiveness and equity of forest restoration in relation to local communities’¹⁸.

6. Traditional Knowledge

One of the core delivery principles of all GCBC projects is the requirement to consider and integrate local and Indigenous knowledge into research. It is therefore unsurprising that this was prominent in the approaches of our projects. A few selected responses variously show how Indigenous and local knowledge has made fundamental contributions.

In Ethiopia it was found that community members were more willing to collaborate when their knowledge was treated as important and central¹⁹. Whilst for a project in Colombia, the belief that IPLCs hold valuable knowledge was considered the starting point for the project²⁰.

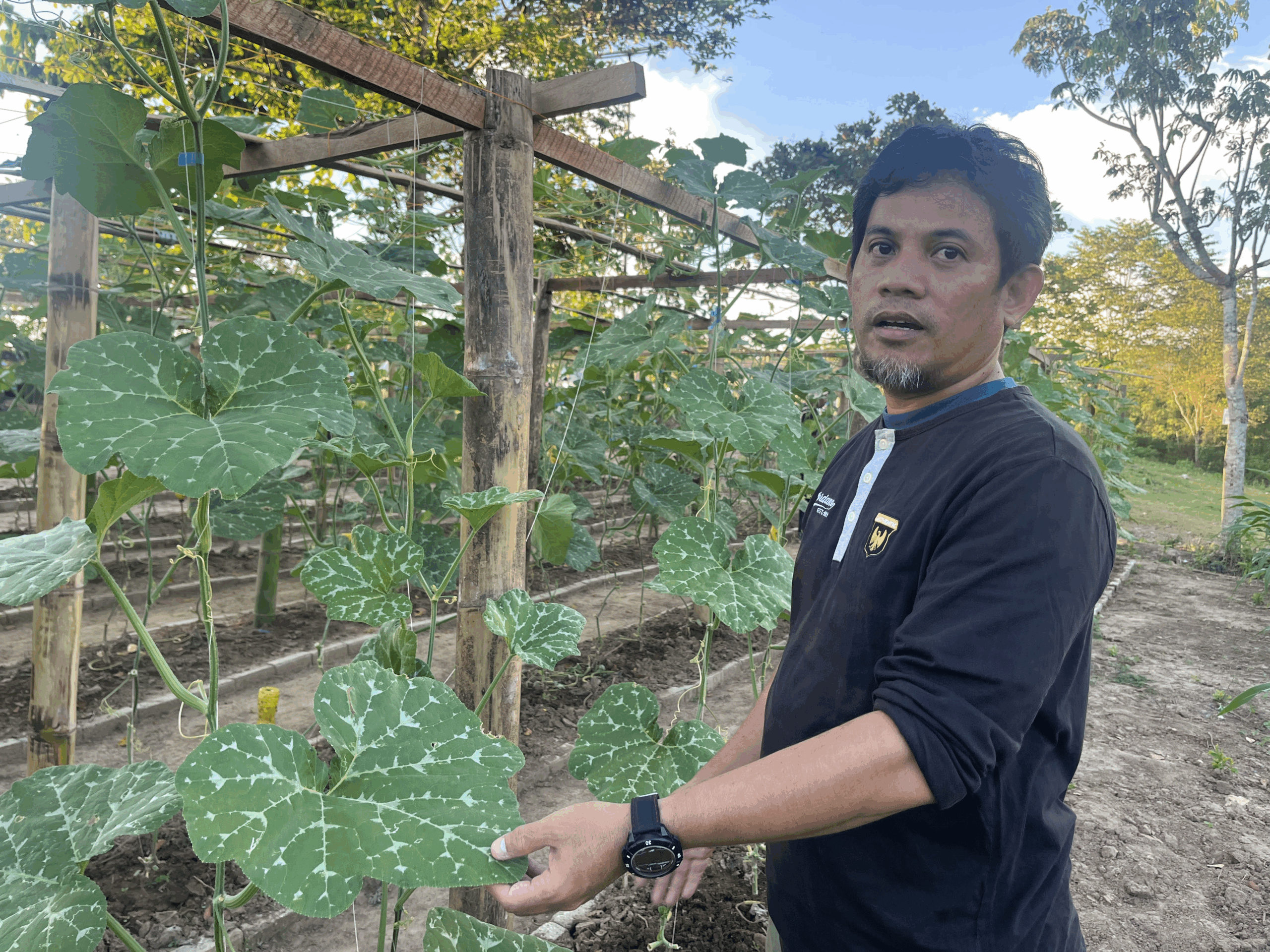

From another project in Colombia, there is recognition that Indigenous and local knowledge has transformed the way the project is conceptualised and supported²¹. In Indonesia it was noted that understanding food and land management practices led to a better appreciation of how food security is currently addressed²².

7. Shared Benefits

The production of knowledge through research alone does not guarantee that Indigenous Peoples and local communities will benefit. Ensuring that communities gain from the process is therefore a key challenge for GCBC projects. For example, a project in Ecuador found that community engagement deepens when they perceive direct, equitable benefits, such as training and technical assistance²³.

In the Cham Islands in Viet Nam the project has learnt that engagement requires continuous consultation, mutual trust, and tangible local benefits²⁴. Training was also noted from Kenya as one of various tangible short-term benefits that could strengthen participation whilst longer term project outcomes were yet to be delivered²⁵.

“We believe that IPLCs should benefit tangibly and intangibly from our research”²⁶.

8. Trust

Beyond the specific points noted above, a particular issue permeates and unites the responses. That issue is trust. Many of the responses were, explicitly or implicitly, about how trust is built between researchers and communities and how trust leads to better research outcomes.

-

-

- Building trust is essential; this means recognising community knowledge systems, ensuring transparent communication and co-developing research goals²⁷.

- An emerging insight from the first stakeholder workshop is that successful integration of traditional and scientific knowledge depends on long-term dialogue andtrust-building²⁸.

- Securing the genuine engagement of local and Indigenous communities requires creating relationships grounded in mutualtrust, cultural respect, and continuous communication²⁹.

- Field visits and workshops, where researchers listen before proposing solutions, have also been essential to build trust and gain a better understanding of real-world challenges farmers are faced with³⁰.

- Trust has been built through regular consultations with local fishers and community representatives on seagrass habitats, ensuring their knowledge informs research design and monitoring³¹.

-

Reflections on Inclusive Research

The eight key points above represent a snapshot of current thinking and practice across GCBC projects. Whilst the responses touch on many interrelated issues, they highlight that our projects strive to be participatory in their approach to working with IPLCs and use a variety of participatory tools to guide their research.

Although these insights do not capture the entirety of the understanding gained, nor are they a complete guide to doing research with IPLCs, they offer valuable lessons and guidance.

More detailed and specific guidance for research with IPLCs is provided by Newing et al (2024)³². Their work is derived from interactions with a wider set of researchers and projects than informs our survey and consequently covers a wider range of issues. Whilst there are areas of notable similarity between their fourteen principles, and the experiences emerging from our survey, both deserve consideration when planning research with IPLCs.

Finally, ensuring that rights holders such as IPLCs are fully engaged in conservation action is not just a research issue, but relevant to all aspects of the planning and implementation of environmental conservation.

Recognising this, Principles for Inclusive Nature Action have been developed by Defra to place equitable, rights-based inclusion at the centre of all biodiversity action. GCBC supports the implementation of those principles.

Endnotes

1. Contributions of Indigenous Knowledge to ecological and evolutionary understanding. Jessen et al 2021 https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2435

2. Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute: Forest Restoration on Indigenous Lands: Restoring Biodiversity for Multiple Ecosystem Services, Community Resilience and Financial Sustainability through Locally Informed Strategies and Incentives

3. Bioversity International: Deploying Diversity for Resilience and Livelihoods

4. The Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (WWT) Following the Water: Participatory Research to Understand Drivers and Nature-based Solutions to Wetland Degradation in Madagascar

5. Fundación Tropenbos Colombia: Creation of an Intercultural Biodiverse Seed Bank with the Indigenous “Resguardo Puerto Naranjo” for Enhancing Restoration and Conservation Efforts in Degraded Areas in the Colombian Amazon

6. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): Nature Nuture

7. International Potato Center (CIP): Andean Crop Diversity for Climate Change

8. Oxford University: The Flourishing Landscapes Programme

9. The Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS): GlobalSeaweed-SUPERSTAR: Supporting livelihoods by Protecting, Enhancing and Restoring biodiversity by Securing the future of the seaweed Aquaculture industry in developing countries

10. Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), USA: SARIKA: Scientific Action Research for Indigenous Knowledge Advancement: Recognising and Rewarding the Contribution of Indigenous Knowledge for the Sustainable Management of Biodiversity

11. UTPL: BIOAMAZ: Realising the potential of plant bioresources as new economic opportunities for the Ecuadorian Amazon: developing climate resilient sustainable bioindustry

12. University of Greenwich: Nature based solutions for climate resilience of local and indigenous communities in Guatemala

13. University of Aberdeen: Cataloguing and Rating of Opportunities for Side-lined Species in Restoration of Agriculturally Degraded Soils in Sub-Saharan Africa (CROSSROADS)

14. University of Lincoln: NATIVE: Sustainable Riverscape Management for Resilient Riverine Communities

15. The Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS): GlobalSeaweed-SUPERSTAR: Supporting livelihoods by Protecting, Enhancing and Restoring biodiversity by Securing the future of the seaweed Aquaculture industry in developing countries

16. University of Birmingham: Building adaptive fisheries governance capacity

17. International Potato Center (CIP): Andean Crop Diversity for Climate Change

18. Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute: Forest Restoration on Indigenous Lands: Restoring Biodiversity for Multiple Ecosystem Services, Community Resilience and Financial Sustainability through Locally Informed Strategies and Incentives

19. University of Leeds: Biodiversity potential for resilient livelihoods in the Lower Omo, Ethiopia

20. Fundación Tropenbos Colombia: Creation of an Intercultural Biodiverse Seed Bank with the Indigenous “Resguardo Puerto Naranjo” for Enhancing Restoration and Conservation Efforts in Degraded Areas in the Colombian Amazon

21. Corporación de Investigación y Acción Social y Económica (CIASE): Gran Tescual Indigenous Reservation Climate Plan

22. University of Sussex: Exploring sustainable land use pathways for ecosystems, food security and poverty alleviation: opportunities for Indonesia’s food estate program

23. Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral (ESPOL): Empowerment of coastal communities in sustainable production practices in Ecuador

24. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF): Translating Research into Action for Livelihoods and Seagrass (TRIALS) – Establishing scientific foundation for seagrass restoration and blue carbon potential, with sustainable livelihood development for coastal communities in Central Vietnam

25. CSIR-CRI, EMBRACE: Engaging Local Communities in Endangered Trees and Minor Crops Utilization for Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihood Enrichment

26. The Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS): GlobalSeaweed-SUPERSTAR: Supporting livelihoods by Protecting, Enhancing and Restoring biodiversity by Securing the future of the seaweed Aquaculture industry in developing countries

27. University of Aberdeen: Cataloguing and Rating of Opportunities for Side-lined Species in Restoration of Agriculturally Degraded Soils in Sub-Saharan Africa (CROSSROADS)

28. Lancaster University: Enabling large-scale and climate-resilient forest restoration in the Eastern Amazon

29. UTPL: Realizing the potential of plant bioresources as new economic opportunities for the Ecuadorian Amazon: developing climate resilient sustainable bioindustry

30. Oxford University: The Flourishing Landscapes Programme

31. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF): Translating Research into Action for Livelihoods and Seagrass (TRIALS) – Establishing scientific foundation for seagrass restoration and blue carbon potential, with sustainable livelihood development for coastal communities in Central Vietnam

32. ‘Participatory’ conservation research involving indigenous peoples and local communities: Fourteen principles for good practice. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110708

Photo Credits

-

Header image and Photo 1: Fisherman on Lake Sofia, Madagascar. Used with permission from the Wildlife and Wetlands Trust.

-

Photo 2: Sam At Rachana and Pin Plil, members of the CIPO research team, with Mr Treub Thaeum, Chief of the Bunong Indigenous community at Pu Kong, in the Brey Ngak sacred forest of the Bunong people, Cambodia. Photographer: Tong Len.

-

Photo 3: Women from the Pasto community outside their restaurant initiative in the resguardo, Colombia, with Daniela Torres, Mama Genith Quitiaquez, Taita Vicente Obando, Ricardo Ibarguen, Wendy Toro and Rosa Emilia Salamanca (Corporación de Investigación y Acción Social y Económica – CIASE).

-

Photo 4: Researchers and local community members from the Bioamaz project during a workshop on safeguards and plant socialisation in the Shuar San Antonio Community, Ecuador.